Review Article Debriefing Critical Incidents in the Emergency Department

- Research commodity

- Open up Access

- Published:

Baseline well-being, perceptions of critical incidents, and openness to debriefing in customs hospital emergency department clinical staff before COVID-19, a cross-sectional report

BMC Emergency Medicine volume 20, Article number:82 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

Groundwork

Emergency department personnel routinely show to traumatic experiences and critical incidents that can touch their own well-being. Peer support through debriefing has demonstrated positive impacts on clinicians' well-beingness post-obit critical incidents. This study explored community hospital emergency department staff'southward perceptions of critical incidents, assessed openness to debriefing and measured baseline well-being. Our analysis provides a baseline of provider well-being immediately prior to the local onset of COVID-19. The potential need for boosted resources to support frontline providers during the pandemic tin can exist evaluated.

Method

We conducted a cross-sectional study for four-weeks prior to the first COVID-19 case in Connecticut using a survey offered to an interprofessional grouping of emergency department clinical staff. The master outcome measures were the Hospital Anxiety and Low Calibration (HADS) and the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) calibration. Pearson's chi-square test was used to identify significant differences in perceptions of disquisitional incidents and debriefings betwixt professional categories. One-manner ANOVA and Tukey'south examination were used to analyze pregnant differences in well-being between professional categories.

Results

Thirty-nine clinical personnel from St. Vincent's Emergency Department responded to the survey. Events frequently selected equally disquisitional incidents were caring for critically sick children (89.seven%), mass casualty events (84.6%), and death of a patient (69.ii%). Disquisitional incidents were unremarkably reported (81.6%) equally occurring once per week. Additionally, 76.2% of participants reported wanting to discuss a critical incident with their squad. Across all respondents, 45.7% scored borderline or aberrant for anxiety, 55.9% scored moderate for burnout, and 55.viii% scored moderate to high for secondary traumatic stress.

Conclusions

At baseline, providers reported caring for critically ill children, mass prey events, and death of a patient as disquisitional incidents, which typically occurred once per calendar week. Death of a patient occurs at increased frequency during the protracted mass casualty experience of COVID-19 and threatens provider well-beingness. Receptiveness to post-event debriefing is high but the method is nonetheless underutilized. With nearly half of staff scoring borderline or aberrant for feet, exhaustion, and secondary traumatic stress at baseline, peer support measures should be implemented to protect frontline providers' well-existence during and afterward the pandemic.

Background

Emergency department clinical staff manage traumatic events as a routine part of their careers in medicine. Although these staff members accept non experienced the patient's trauma get-go-hand, the strong emotional reactions providers may experience following caring for patients who have experienced such events tin impact them in many means; including cognitively, behaviorally, emotionally, and physically [1,2,iii,4]. As a result, frontline healthcare workers are at hazard for secondary traumatic stress responses that range from exhaustion and abstention to hypervigilance, physical affliction, and presenteeism [5, 6]. At baseline, healthcare workers report high levels of burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and suicidal ideation, which are correlated to decreases in performance and patient intendance [2, 7,8,9,10,11]. The new demands placed on providers past COVID-19 volition likely negatively impact providers' mental health [12, xiii]. An earnest assessment of the utilization of stress mitigation strategies must be conducted for the protection of frontline providers.

Discussion-based stress interventions in real time (in situ) take been developed to amend peer back up well-being and providers' ability to return to work, while reducing stress manifestations [xiv, 15]. Critical incident stress debriefing (CISD), an older and more structured class of debriefing, has come under scrutiny for perhaps worsening PTSD symptoms or secondary traumatic stress. Notably, the literature that suggests these agin outcomes included studies which used CISD exterior the model'south intended framework, such that debriefing occurred 1-on-1 with patients instead of in a group setting with frontline providers [sixteen, 17]. Newer methods of postal service-consequence debriefing, such every bit the INFO and DISCERN models, [18, nineteen] are structured to avoid many of the perceived pitfalls of CISD through their more firsthand timing and provider-implemented way [20]. In this newspaper, the term "debriefing" will be used to indicate a grade of peer support, give-and-take-based stress intervention.

These low resource methods have demonstrated efficacy for interprofessional staff following pre-selected clinical events or critical incidents [21,22,23,24]. A critical incident has been defined by Magyar et al equally, "a self-defined traumatic outcome that causes individuals to experience such stiff emotional responses that usual coping mechanisms are ineffective" [25]. Pediatric and adult resuscitations are common pre-selected clinical events which should initiate a debriefing [14, 19, 24, 26]. Clinical events previously recognized as sorry for staff or cited every bit critical incidents in the literature include decease of a patient, multi-trauma, and death of young patients [one, 19, 27]. To cope with emotionally challenging patient cases, nurses have previously reported reliance upon peer support and physicians have voiced a preference for a more formal back up structure [22, 23, 26].

The aim of this study is to describe the well-being of community hospital emergency department clinical staff immediately prior to the local onset of COVID-nineteen and identify their perceptions surrounding critical incidents and post-upshot, word-based interventions. The electric current low level of infirmary instituted peer support programs and electric current risks to health professionals' well-being needs to be addressed [28]. By demonstrating healthcare workers' openness to peer support, this report serves every bit an testify-based call to action for the implementation of in situ debriefing to mitigate stress impacts during the pandemic.

Methods

Study design

This cross-exclusive study was conducted in the four-weeks immediately prior to the announcement of the first COVID-19 positive case in a Connecticut country resident [29]. The study site was a community hospital emergency department with no formal peer back up debriefing program, akin to most community hospitals [27, 30]. Survey distribution began in February 2020 and responses were collected through early on March 2020. The study used self-report questionnaires in Qualtrics, a secure HIPAA compliant HITRUST certified survey software published past Qualtrics, to collect demographic data from the interprofessional group of respondents. The survey questions collected staff's experiences and perspectives surrounding disquisitional incidents and post-event give-and-take-based interventions. Levels of anxiety, low, burnout, compassion satisfaction, and secondary traumatic stress were measured using validated clinical questionnaires and scoring scales, described beneath in more detail. All survey responses were nerveless anonymously.

Written report participants

The online survey was distributed through a department-wide eastward-post to all emergency section clinical staff at a customs hospital in Connecticut. Study participants encompassed the following clinical roles: registered nurses (RN), physician administration (PA), physicians, resident physicians, and emergency department technicians (ED Tech).

Demographic data

Demographic data collected from the participants included gender, clinical office, and years of practice.

Critical incidents

Participants were given the post-obit definition for a critical incident prior to responding to questions regarding their experiences and perspectives, "A critical incident is a self-divers traumatic outcome that causes individuals to experience such strong emotional responses that usual coping mechanisms are ineffective."

Hospital anxiety and low scale (HADS)

The HADS was used to mensurate the levels of anxiety and depression in the medical staff [31,32,33]. The HADS questionnaire contained xiv items, seven items relevant to each feet and depression, graded for experience within the past 7 days. Each item was scored between 0 and 3 and the scores within each category were totaled for a cumulative score ranging 0–21. Higher scores indicate more aberrant levels of feet and low.

Professional quality of life (ProQOL)

The ProQOL version 5 assessment was used to measure the levels of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress in the medical staff [34, 35]. The ProQOL is a five-betoken Likert calibration consisting of xxx items. Scores cumulate within each of the three outcome measures for a total score ranging from x–50. Higher scores indicate college levels of pity satisfaction, exhaustion, and secondary traumatic stress.

The ProQOL defines measures in the post-obit ways, "Pity satisfaction is about the pleasure you derive from existence able to practise your piece of work well" [36]. Secondary traumatic stress is the development of emotional duress due to indirect exposure to trauma derived while helping others [37].

Statistical analysis

For chiselled variables, including demographic data and self-report data regarding critical incidents, proportions were reported. Pearson'southward chi-square test was used to further analyze for associations between professional person categories and responses to critical incident and debriefing questions. Due to the small-scale sample size, the registered nurse and doc assistant professional categories were collapsed into a single group. Outcomes of the HADS and ProQOL scales were reported as proportions and one-way ANOVA was employed to assess for differences between hateful well-being scores and demographic groups. Further analysis of statistically significant findings was conducted with Tukey's post hoc test. All P-values were two-sided and, if below 0.05, the results were considered statistically meaning. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA).

Results

Participants

In total, 46 people consented to the survey. For this written report, seven respondents who did not respond to all questions or returned the survey after the first positive COVID-19 local case were excluded, leaving a sample of 39. This sample represents 32.5% of the emergency department's 120 employees.

A total of 39 staff members (6 physicians, 27 combined registered nurses and physician assistants, and 6 emergency department technicians) completed the demographics and opinion portion of the survey, 35 staff members (5 physicians, 24 registered nurses and physician administration, and six emergency department technicians) completed the HADS, and 34 staff members (four physicians, 24 registered nurses and doctor assistants, and half dozen emergency section technicians) completed the ProQOL. The demographic data of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Disquisitional incidents

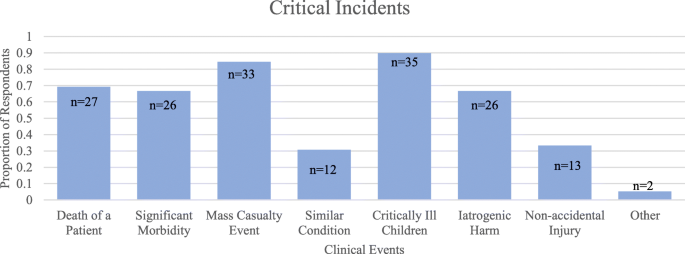

The clinical event most normally selected as a disquisitional incident was "caring for a critically ill child" by 89.74% (n = 35) of respondents. Frequency of clinical events considered disquisitional incidents are shown in Fig. 1. The "Other" category consisted of two respondents who wrote in "death of a kid."

Proportion of respondents, out of 39, who considered each clinical event a disquisitional incident

The proportion of respondents who selected each clinical consequence are shown by professional category in Table 2. Pearson's chi-foursquare assay was used to identify the associations betwixt clinical role or years of practice and clinical events considered critical incidents. There was a statistically significant clan between selection of mass casualty event as a critical incident and clinical role (χ(1) = 6.850, p = .033), with fifty% selection amongst emergency section technicians compared to 83.3% of physicians and 92.half-dozen% of registered nurses and medico assistants. In that location was no statistically significant association between any clinical events and years of do.

The proportion of participants who reported participating in a critical incident during the final 12 months was 97.four% (n = 38) and the most common frequency for critical incidents was reported as "one time per week" by 81.vi% (n = 31) of respondents (Table 3).

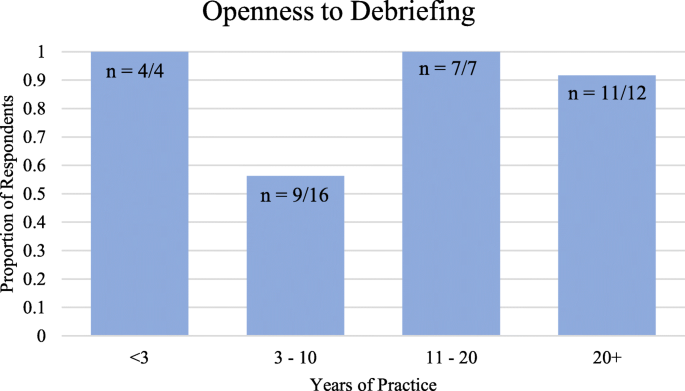

Openness to debriefings

The proportion of respondents who reported having discussed a critical incident with their team during the past 12 months was 64.1% (north = 25) and 100% (n = 25) of those respondents reported finding information technology useful to their well-being. Of all respondents, 79.5% (northward = 31) reported wanting to discuss a critical incident with their team in the past 12 months. There was a statistically meaning clan between desire to discuss a critical incident and years of practice (χ(1) = 9.229, p = .026), with the highestproportion from the < 3 years of exercise (100%, northward = 4) and 11–20 years of practise (100%, n = 7) groups and the everyman proportion amongst the 3–x years of practice group (56.3%, n = 9) as shown in Fig. ii. There was no statistically pregnant clan between wanting to discuss a critical incident and clinical function (χ(1) = 0.725, p = .696).

Proportion of respondents, past years of practice, who reported wanting to discuss a critical incident with their team

Baseline well-existence

The levels of anxiety and low equally measured by the HADS and levels of compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress equally measured past the ProQOL have been reported in Table 4.

There was a statistically significant difference between clinical roles for hateful secondary traumatic stress scores as adamant by one-way ANOVA (F (2, 31) = 5.811, p = .007). A Tukey post-hoc examination revealed that secondary traumatic stress was statistically significantly lower in the combined RN/PA grouping (21.46 ± 6.043) compared to ED Techs (30.83 ± 6.369, p = .011). There was no statistically significant difference between the physicians and ED Techs (p = .115) or registered nurses and md administration (p = .987). There was no statistically significant deviation between the gender or years of practice groups for mean secondary traumatic stress scores or between whatever groups for the remaining HADS and ProQOL measures.

Give-and-take

Critical incidents

Prior to the local onset of COVID-19 in Connecticut, the majority of frontline providers in this study identified caring for critically ill children (89.7%), mass casualty events (84.six%), and death of a patient (69.2%) as critical incidents that would render usual coping mechanisms ineffective. These findings are consistent with a descriptive, cross-sectional study conducted in xiii pediatric emergency departments across Australia and New Zealand, which constitute 81% of senior nurses and physicians believed decease of a patient was a critical incident warranting debriefing [27]. At baseline, critical incidents were predominantly reported at a frequency of just in one case per week past 81.half-dozen% of providers. Perceptions of what clinical events are critical incidents may also exist impacted in the postal service-COVID-nineteen mural. Specifically, "caring for a patient with a status that you lot or a loved one has," which had the lowest respondent option (thirty.8%), may increment in prevalence due to the potential development of fear amongst healthcare providers regarding contracting or transmitting COVID-19 to family members.

Openness to debriefings

The majority of participants indicated a desire to discuss a critical incident with their team in the past 12 months, demonstrating a receptiveness to in situ stress interventions similar mail service-event discussions or debriefings. There was a statistically significant deviation between the proportion of providers who wanted to hash out a critical incident across years of practise; with the 3–10 years of practice group reporting the lowest proportion (56.iii%), compared to 100% of providers with < 3 and 11–twenty years of practice or 91.seven% of providers with xx+ years of practice. The lower charge per unit amid mid-career providers may be attributed to self-perceptions of resilience. These outcomes reveal an opportunity for specific programming aimed at normalizing and promoting peer back up among providers with 3–10 years of practice. Given the high charge per unit of receptiveness across providers with more years of practice, this may also create a channel for senior mentorship to improve receptiveness across inferior mentees.

There was no difference in openness to post-outcome discussion across clinical roles, further indicating potential for high uptake by interprofessional teams. Previous studies conducted in pediatric emergency department nurse populations have reported like preferences for peer based support following critical incidents [22]. Given the potential use of travel nurses and outside medical providers to supplement hospital staffing, hands self-implemented, low-resource debriefings may provide foundation for building peer back up amongst less familiar teams.

Baseline well-being

Roughly one-half of all medical workers surveyed experienced deadline or abnormal anxiety (45.seven%), moderate exhaustion (55.9%), or moderate to loftier secondary traumatic stress (55.eight%). This level of burnout is consistent with previously reported levels of dr. exhaustion. A phone call to action by the Massachusetts Medical Society in 2019 already considered the country of physician well-beingness a public wellness crisis [9]. Healthcare workers, who may face disillusionment as a result of this pandemic, would benefit from wider accessibility to various forms of stress interventions [38].

To our noesis, this study is the offset to report baseline well-beingness, opinions of critical incidents, and openness to debriefing amongst emergency department clinical staff immediately prior to the local onset of COVID-19. Several limitations of the report should be noted. The historic period of respondents was not collected in demographic information, although it would have been interesting to correlate the age of respondents with their markers of well-being. The small sample size collected at a single site reduces the ability to find group differences and the ability to generalize from the findings. Additionally, nonresponse bias may have influenced our findings. Providers who completed surveys may accept had stronger feelings regarding mental health support compared to providers who declined, resulting in an unrepresentative sample. Baseline well-being may differ for emergency departments with institutionalized peer support programs.

At nowadays, a longitudinal study aims to capture weekly impacts from critical incidents within this aforementioned population in order to assess how evolving COVID-19 cases manifest as critical incidents and effect provider well-being through time. Future plans include reassessment of HADS, ProQOL, and perceptions of critical incidents and debriefings after COVID-xix cases decrease to directly assess the bear upon of the pandemic on providers. Hospitals should also aim to collect local data on provider well-being, implement post-event stress debriefings, and assess stress mitigation interventions for efficacy.

Determination

Our cross-sectional report of community hospital emergency section clinical staff in one institution found providers considered mass casualty events and decease of a patient to exist disquisitional incidents. At baseline, providers experienced levels of anxiety, exhaustion, and secondary traumatic stress at levels previously identified as detrimental to personal and public health. All respondents who had discussed a critical incident with their team found this feel useful to their wellbeing. The majority of providers, including those with no prior debriefing experience, reported a desire for mail service-effect, team-based discussions. The absence of institution supported debriefings and peer support groups in customs hospitals is an surface area for improvement and discussion-based stress reduction interventions could be included in COVID-xix response trainings to promote peer support and frontline provider well-being.

This report was conducted prior to the onset of the pandemic, and in light of the likelihood of increased negative mental health impacts from COVID-19, this data may indicate a peculiarly vulnerable position for providers. Acute and potentially enduring moral injury sustained from the potential shortages of appropriate proper protective equipment (PPE), lack of evidence based data to inform conclusion making, crisis standards of intendance, and the trauma of witnessing big numbers of individuals experiencing serious illness and death in the absence of family may all contribute to high levels of stress among frontline healthcare providers during and after the pandemic. These experiences are compounded by the stress of social isolation and lack of appropriate human interactions that would otherwise mitigate stress. Researchers will likely find significant impairments in feet, exhaustion, and secondary traumatic stress as the lingering effects of COVID-xix effect frontline workers. Peer back up measures that facilitate debriefings should be implemented to protect frontline providers' well-being during and after the pandemic.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are bachelor from the corresponding writer on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HADS:

-

Hospital feet and depression scale

- ProQOL:

-

Professional quality of life

- ED Tech:

-

Emergency department technician

- RN:

-

Registered nurse

- PA:

-

Physician assistant

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus virus affliction 2019

References

-

Blacklock East. Interventions following a disquisitional incident: developing a critical incident stress direction team - ScienceDirect. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2012;26:2–viii.

-

Glasberg AL, Eriksson Southward, Norberg A. Exhaustion and 'stress of conscience' among healthcare personnel. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57(4):392–403.

-

Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2214–36.

-

Maloney C. Critical incident stress debriefing and pediatric nurses: an approach to support the piece of work environment and mitigate negative consequences. Pediatr Nurs. 2012;38(2):110–3.

-

Penix EA, Kim PY, Wilk JE, Adler AB. Secondary traumatic stress in deployed healthcare staff. Psychol Trauma 2019;11(i):i–ix.

-

Guitar NA, Molinaro ML. Vicarious trauma and secondary traumatic stress in wellness care professionals. UWOMJ. 2017;86(2):42–3.

-

Tawfik DS, Turn a profit J, Morgenthaler TI, Satele DV, Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, et al. Physician burnout, well-beingness, and work unit of measurement safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(11):1571–fourscore.

-

Fred HL, Scheid MS. Physician burnout: causes, consequences, and (?) cures. Tex Heart Inst J. 2018;45(four):198–202.

-

Jha AK, Iliff AR, Chaoui AA, Defossez S, Bombaugh MC, Miller Yr. A crunch in health care: a call to action on physician burnout. 2019.

-

Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-existence: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–46.

-

Gazoni FM, Durieux ME, Wells 50. Life after death: the aftermath of perioperative catastrophes. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(2):591–600.

-

Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li 50. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-nineteen pandemic: a cross-exclusive report. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112936.

-

Xiao H, Zhang Y, Kong D, Li S, Yang North. The effects of social support on sleep quality of medical staff treating patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-nineteen) in January and February 2020 in China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:923549.

-

Copeland D, Liska H. Implementation of a post-code pause: extending post-event debriefing to include silence. J Trauma Nurs. 2016;23(2):58–64.

-

Harder N, Lemoine J, Harwood R. Psychological outcomes of debriefing healthcare providers who experience expected and unexpected patient death in clinical or simulation experiences: a scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(3–iv):330–46.

-

Rose SC, Bisson J, Churchill R, Wessely S. Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;two:1–49.

-

van Emmerik AA, Kamphuis JH, Hulsbosch AM, PMG E. Unmarried session debriefing after psychological trauma: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2002;360(9335):766–71.

-

Rose Southward. Accuse nurse facilitated clinical debriefing in the emergency department | Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine | Cambridge Cadre. 2018; Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/canadian-journal-of-emergency-medicine/article/charge-nurse-facilitated-clinical-debriefing-in-the-emergency-department/CC224433937ACBA849491A66EBC9593D. Accessed 04/xv/, 2020.

-

Mullan PC, Wuestner E, Kerr TD, Christopher DP, Patel B. Implementation of an in situ qualitative debriefing tool for resuscitations. Resuscitation. 2013;84(7):946–51.

-

Kessler D. Debriefing in the emergency department after clinical events: a practical guide. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;65(six):690–8.

-

O'Connor J, Jeavons South. Perceived effectiveness of critical incident stress debriefing by Australian nurses. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2003;20(4):22–nine.

-

Clark PR, Polivka B, Zwart Yard, Sanders R. Pediatric emergency department staff preferences for a critical incident stress debriefing. J Emerg Nurs. 2019;45(4):403–x.

-

Zheng R, Lee SF, Bloomer MJ. How nurses cope with patient death: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(one–2):e39–49.

-

Cheng A, Hunt EA, Donoghue A, Nelson-McMillan Thousand, Nishisaki A, LeFlore J, et al. Examining pediatric resuscitation teaching using simulation and scripted debriefing: a multicenter randomized trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(6):528–36.

-

Magyar. Review article: debriefing critical incidents in the emergency section. Emerg Med Australas 2010;22:499–506.

-

Gillen J, Koncicki ML, Hough RF, Palumbo K, Choudhury T, Daube A, et al. The touch on of a fellow-driven debriefing programme afterwards pediatric cardiac arrests. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):272.

-

Theophilos T, Magyar J, Babl FE. Debriefing critical incidents in the paediatric emergency section: electric current practice and perceived needs in Australia and New Zealand. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;21(six):479–83.

-

Gougoulis A, Trawber R, Hird K, Sweetman K. 'Take x to talk well-nigh information technology': Utilise of a scripted, mail service-event debriefing tool in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Paediatr Kid Wellness. 2020;56(vii):1134–9. https://doi.org/x.1111/jpc.14856. Epub 2020 Mar xx. PMID: 32196132.

-

The Role of Governor Ned Lamont. Governor Lamont Announces First Positive Case of Novel Coronavirus Involving a Connecticut Resident [press release] (03/08/2020) [cited 2020 Apr 2]. Available from: https://portal.ct.gov/Role-of-the-Governor/News/Press-Releases/2020/03-2020/Governor-Lamont-Announces-Starting time-Positive-Instance-of-Novel-Coronavirus-Involving-a-Connecticut-Resident.

-

Ireland Due south, Gilchrist J, Maconochie I. Debriefing subsequently failed paediatric resuscitation: a survey of current UK exercise. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(6):328–30.

-

Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;one:29.

-

Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63(0):1–eleven.

-

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the hospital feet and depression scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52(two):69–77.

-

Hemsworth D, Baregheh A, Aoun S, Kazanjian A. A critical research into the psychometric properties of the professional person quality of life scale (ProQol-five) musical instrument. Appl Nurs Res. 2018;39:81–8.

-

Beaumont E, Durkin M, Martin CJH, Carson J. Measuring relationships betwixt cocky-compassion, compassion fatigue, burnout and well-existence in student counsellors and student cognitive behavioural psychotherapists: a quantitative survey. Couns Psychother Res. 2016;16(1):15–23.

-

The Heart for Victims of Torture. Professional Quality of Life Mensurate. Available at: https://www.proqol.org/ProQol_Test.htmlfiles/534/ProQol_Test.html. Accessed 15 April 2020.

-

Figley CR. Compassion fatigue: Toward a new understanding of the costs of caring. In: Secondary traumatic stress: Cocky-care issues for clinicians, researchers, and educators. Baltimore, MD, US: The Sidran Press; 1995. p. iii–28.

-

Myers D, David F. Disasters in Mental Health Services A Primer for Practitioners Psychosocial. DHHS 2005;publication no. ADM 90–358.

-

Laura Cantu. Quick Tip for Healthcare Providers - Defusing on Shift. 2020 April 10,;https://youtu.exist/9XOaBP9073M.

Acknowledgements

Richard S. Feinn, PhD provided statistical guidance and assay support.

Linda Durhan, MD provided technical writing guidance.

Authors' information (optional)

LT is an emergency medicine physician at St. Vincent's Medical Center and associate professor of medical sciences at Frank H. Netter Dr. School of Medicine.

LC is a third-yr medical student who has given a TEDx Talk on md well-beingness in add-on to self-publishing a debriefing tutorial video for coping with COVID-19 on shift (YouTube: Quick Tip for Healthcare Providers - Defusing on Shift) [39].

Funding

Capstone Project Funding provided by Frank H. Netter Physician School of Medicine, Scholarly Reflection & Capstone/Concentration Course. The funder, Frank H. Netter Physician School of Medicine, provided a set corporeality of capstone funding for all medical students. They did not participate in project development or data collection in any way.

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

LC analyzed and interpreted the survey data and was the major contributor in writing the manuscript. LT guided protocol design and directed data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Upstanding considerations for this study in regard to the use of human subjects were approved by the St. Vincent's Medical Center IRB. We obtained written consent from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

LC and LT are currently researching the efficacy of debriefing methods for interprofessional use in acute care settings.

The authors have no other competing interests to declare.

Boosted information

Publisher'southward Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Artistic Commons Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, equally long every bit you requite appropriate credit to the original author(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other 3rd party material in this article are included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article'due south Creative Commons licence and your intended utilise is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted employ, y'all will demand to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/ane.0/) applies to the data fabricated available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this article

Cite this article

Cantu, L., Thomas, Fifty. Baseline well-being, perceptions of critical incidents, and openness to debriefing in community hospital emergency department clinical staff earlier COVID-19, a cross-sectional study. BMC Emerg Med 20, 82 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-020-00372-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12873-020-00372-5

Keywords

- Debriefing

- Peer support

- Well-being

- HADS

- ProQOL

- Critical incident

- COVID-19

- Secondary traumatic stress

- Burnout

fredericminch1949.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmcemergmed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12873-020-00372-5