Collagen Injection for Vocal Cord Paralysis

- Original research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Evaluating the timing of injection laryngoplasty for vocal fold paralysis in an attempt to avoid future blazon 1 thyroplasty

Journal of Otolaryngology - Caput & Neck Surgery book 42, Commodity number:24 (2013) Cite this article

Abstract

Objectives

To determine whether immediate (less than three months from time of nerve injury), early (from iii to 6 months from time of nerve injury) or late (more than vi months from fourth dimension of nerve injury) vocal fold injection influences the long-term outcomes for patients with permanent unilateral vocal fold paralysis.

Methods

A total of 250 patients with documented unilateral vocal fold paralysis were identified in this retrospective chart review. 66 patients met the inclusion criteria, having undergone awake trancervical injection with gelfoam™, collagen, perlane™ or a combination. Patients with documented recovery of vocal fold mobility, or patients with less than 1 year of follow-up afterward the onset of paralysis were excluded. Patients were stratified into immediate (<3 months), early (3-vi months) and late (>half-dozen months) groups denoting the time from suspected injury to injection. The demand for open surgery as determined by a persistently immobile song fold with bereft glottic closure post-obit injection was the primary outcome.

Results

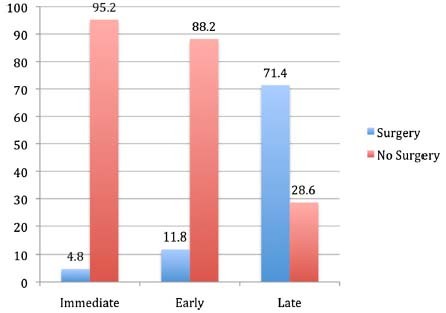

ane out of 21 (4.8%) in the immediate grouping, 2 out of 17 (eleven.8%) in the early group and twenty out of 28 (71.iv%) in the late grouping required type 1 thyroplasty procedures to restore glottic competence. There was significance when comparison tardily injection to both early on and immediate injection (p < 0.001). No statistically significant differences were seen when comparing the number of injections needed to restore glottic competence.

Conclusions

This x-twelvemonth longitudinal cess revealed that early medialization of a permanent paralyzed, abducted song fold with a temporary material appears to diminish the likelihood of requiring permanent laryngeal framework surgery.

Introduction

Vocal fold immobility is a wide term used to describe vocal folds that are restricted secondary to mechanical fixation or neuropathy. Mechanical fixation may result from an arytenoid dislocation, edema or inflammation of the glottis, or neoplastic invasion. Neurogenic immobility may occur with lesions in the motor cortex or compromise of the recurrent laryngeal nerve due to either surgical iatrogenic injury or extra-laryngeal malignancies at any point along its course from the jugular foramen to the carotid sheath, mediastinum, and either around the subclavian artery on the right or the aortic arch on the left, to the tracheoesophageal groove[1]. The resulting glottic insufficiency may lead to dysphonia, aspiration, and shortness of jiff. Iatrogenic stretching or transection of the recurrent laryngeal nerve may crusade only temporary immobility. However, if there is no recovery, procedures aiming to restore glottic competence include permanent and temporary vocal fold injections (VFI) or laryngeal framework surgery, such every bit blazon 1 thyroplasty.

Different injection materials, either permanent (Teflon, PDMS) or temporary (Gelofoam, Cymetra, Restylane, Radiesse) and dissimilar approaches (transoral vs. percutaneous) take been used to medialize the paretic song fold in order to improve voice and prevent aspiration[2]. Previous approaches to unilateral vocal fold paralysis included waiting several months for spontaneous recovery to be ruled out before proceeding with medialization[3]. Recent bear witness, however, suggests that early intervention reduces the need for transcervical reconstruction[4].

The goal was to evaluate the timing of VFI with respect to eventual demand for blazon 1 thyroplasty. In this retrospective chart review, we study the different parameters available to laryngologists for VFI. Specifically, nosotros compare firsthand, early on and tardily (>3 months, 3-vi months and >half-dozen months, respectively) injection when using dissimilar materials.

Materials and methods

The study was canonical by The Enquiry Ethics Board (REB) of McGill University Health Centre (MUHC). A retrospective chart review between Jan 2000 and Sept 2011 identified all adult patients initially presenting at our Voice center and diagnosed during laryngoscopy with UVFP. Of the 250 patients with unilateral vocal fold paralysis, 66 met the inclusion criteria of having undergone injection medialization as initial treatment within 1 year of onset of their paralysis, and these formed the written report grouping.

Patients were stratified into firsthand (<three months), early on (3-vi months) and late (>6 months) groups denoting the time from suspected injury/onset of dysphonia to injection. All patients in the study had i or more injections. Hyaluronic acid (perlane™) absorbable gelatin (Gelfoam™) or collagen were injected using a trans-cricothyroid technique. Three senior laryngologists performed the injections on these patients in the aforementioned phonation lab – all following the aforementioned technique. They all injected inside each of the immediate, early and late groups. At the time of information collection, 21 patients had injection in <3 months, 17 patients between 3-6 months and 28 had their injections afterwards six months. 51 patients had an identifiable crusade of paralysis (iatrogenic, malignancy or stab injury), fifteen were considered equally idiopathic which was confirmed by routine work-up which may take included CT, MRI, barium consume, thyroid ultrasound, flexible endoscopy and autoimmune workup. Glottic competency was determined based on the patients' subjective voice quality every bit well as objectively using the laryngoscope.

Results

Of the 250 patients with unilateral vocal fold paralysis collected, 66 met the inclusion criteria (31 female, 35 male). The average age of the cohort was 59.5 (range 23 – 84) with no pregnant differences between the immediate, early and late injection groups. All injections were performed percutaneously in the part setting with local anesthesia and about commonly utilized perlane™ (67%). The descriptive statistics detailing cause of vocal fold paralysis, length of follow-up, timing of injection and outcome (open thyroplasty performed or avoided) are included in Table1.

In full, 29/66 of patients had UVFP secondary to an oncologic etiology with 93% (27/29) a upshot of lung cancer. thirty.3% (20/66) of patients had UVFP from iatrogenic etiologies: 17 postal service-surgical and 3 from chemotherapy or radiation therapy. The rest of the cohort suffered glottic incompetence from trauma[2] and 15 from idiopathic processes (Figures1 and2).

Etiology of unilateral vocal fold immobility.

Comparison of need for blazon-1 thyroplasty at Immediate (<3 months), early (3-6 months) versus late (>6 months) groups.

21 patients were stratified into the firsthand grouping (<iii months), 17 patients to the early group (3-6 months) and 28 patients to the late group (>vi months) denoting the time from suspected injury to injection. A mean delay of 42 days for the immediate group, 4.2 months for the early group and 12 months for the belatedly group was observed. The average length of follow upward from the onset of dysphonia was 18 and 19 months for immediate (range 12-48 mothns) and early groups (range 12-36 months) respectively and 32.vii months (range 12-74 months) for belatedly group. 62 patients had left and four had correct UVFP.

Many of the patients in this written report required more than than one injection to achieve glottic competency and a satisfactory voice. Thirty-ix (59.one%) required at to the lowest degree two and fifteen (22.vii%) required at least iii. Ii patients required more than three injections. Eight patients accomplished glottic competency with only 1 injection from the immediate group compared to half-dozen from the early group. Ultimately twenty-three of 66 patients failed to attain glottic competency and required laryngeal framework surgery and xl-3 had documented medialization of the paralyzed vocal fold with a noted improvement in objective and subjective voice quality. Of the twenty-three patients who required laryngeal framework surgery, 1 was from the immediate group (one/21, 4.8%), ii from the early grouping (2/17, xi.8%) and twenty from the late grouping (20/28, 71.four%).

Patients who received injections during the immediate three-month window were 66.7% (95% CI = 47.6 – 85.vii) less likely to undergo surgery than those injected afterwards half dozen months (P <. 001). Patients who received injections during the early on 3 to 6 month window were 59.vii% (95% CI = 37 – 82.iii) less likely to undergo surgery than those injected afterwards 6 months (P <. 001). Just a vii% difference is seen when comparing the immediate vs. early groups (-10.8 – 24.8) (P >. 05).

Discussion

The rationale for medializing a paralyzed truthful vocal fold is to restore glottic competence in order to improve voice quality and preclude aspiration. The optimal fourth dimension and method of vocal fold paralysis management is controversial. Factors contributing to the controversy include dubiousness regarding the possible return of function, and concern nearly the irreversibility of some procedures[v]. Initial handling options for UVFP include temporary vocal fold injection medialization, voice therapy, or observation for spontaneous render of function.

In 1992, Ford and colleagues revolutionized the concept of laryngoplasty with the introduction of a temporary injectable collagen to restore the glottic competence[6]. Since and then, several materials for injections have been developed and are typically described equally either temporary, long lasting or permanent. Long lasting/permanent injectable materials include autologous fat, calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse™), polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS or particulate silicone), and historically, polytef paste (Teflon™)[2]. Temporary injection materials include bovine gelatin (Gelfoam™, Surgifoam™), collagen-based products (Cymetra™, Zyplast™, Cosmoplast/Cosmoderm™), hyaluronic acid (Restylane™, Perlane™, Hyalaform™), and carboxymethylcellulose (Radiesse Vox Gel™)[2].

Understanding the etiology of the paralysis is indeed an essential element of appropriate workup and handling. Rosenthal and colleagues[1] found that the nigh common etiology for unilateral immobility is secondary to surgical iatrogenic injury (thyroid and non-thyroid). Bated from surgery, other common causes of vocal fold paralysis include extralaryngeal malignancy, idiopathic causes and trauma. In our cohort, the bulk of the patients 43.9% (29/66) had UVFP secondary to a malignant etiology followed past 30.three% (20/66) of patients who had UVFP from iatrogenic etiologies. This distribution might be explained by the referral pattern in our establishment and the fact that most of the mail thyroidectomy patients were excluded from our sample considering they regained their nerve role. The left recurrent laryngeal nerve (94%) was more commonly injured in our written report than the right (6%). This is consequent with the prior literatures and can be explained past its longer and more convoluted course.

Previously, it was accepted that waiting several months earlier intervention would allow time for spontaneous recovery to occur. However, due to its ease of use and depression gamble and complication rate, early injection laryngoplasty under topical coldhearted provides an excellent therapeutic option for both patients and md. Awake injection laryngoplasty produces a substantial improvement in voice quality as measured past the Vocalisation-Related Quality of-Life (VRQOL) measure[7]. Moreover, injection laryngoplasty produced improvements in Glottal Office Alphabetize (GFI), GRBAS, Functional outcome swallowing scale (FOSS), and maximum vocalisation fourth dimension measurements, which confirm the advantage of this technique in improving glottic competency[five]. Bhattacharyya et al. compared early and late vocal fold medialization for vocal fold paralysis following thoracic procedures and institute a significantly reduced take chances of post-injection pneumonia and length of hospital stay for the early injected group[8]. Friedman et al. recently hypothesized that with early intervention (less than half-dozen months from time of injury), the implant cloth allows the vocal fold to exist in a more appropriate resting position during the time window of synkinetic reinnervation. It is possible that synkinetic reinnervation permanently maintains a medialized and more favorably positioned vocal fold. Conversely, a non-injected vocal fold which has been causeless a more lateralized (and less favorable) position post-obit synkinetic reinnervation is less likely to be adequately adducted with injection[four]. In fact, there might be a greater caste of benefit to an even earlier acute intervention (i.eastward., sooner than six months afterward paralysis) in terms of decreasing the likelihood of requiring a subsequent permanent laryngeal framework procedure[9].

In our report, which defined immediate intervention to be less than three months mail paralysis, the percentage of patients requiring open surgery post-obit injections because of inadequate long-term results was iv.eight%, which is even lower than (37.five%) what was found by Friedman et al. Just a 7% departure (non statistically pregnant) is seen when comparing the immediate vs. early groups (-10.8 – 24.8). Nevertheless, patients who received injections during the immediate or early window were 66.seven% and 59.vii% (95% CI = 47.half dozen – 85.7) and (95% CI = 37.0 – 82.3) respectively less probable to undergo surgery than those injected later on six months (late group). It is a common misconception that vocal fold paralysis is the result of complete muscle denervation. Animal experiments demonstrate that synkinetic reinnervation occurs in more than 65% of all cases of paralysis, which is thought to be comparable to that in humans[10–12].

Many of the patients in this study required more i injection due to ongoing dysphonia or glottic incompetency. Thirty-ix (59.1%) required at least 2 injections, including thirteen from the firsthand, 11 from the early on, and fifteen from the late groups. Owing to low sample sizes within each group, comparisons between groups are inconclusive. When speaking of recovery, several authors accept described return of function in general terms, noting that "all cases recovered in less than twelve months". All the same, many documented no further recovery after much shorter intervals[thirteen]. Although delayed recovery as long as iv years following onset has been very occasionally been noted[fourteen], assuasive a one twelvemonth interval before assuming the paralysis to be permanent and instituting final treatment would seem reasonable. In our sample, all patients who were lost to follow up in less than one year were excluded. The average of follow upward from the onset of dysphonia was 18 and 19 months for immediate and early groups respectively, 32.7 months for late grouping. Finally, patient historic period has long been recognized as an essential cistron in motor nervus regeneration, and many studies have confirmed this finding[xv]. Response to the injection and/or thyroplasty was non significantly affected by age in our written report.

Our current report has a number of methodologic limitations. First, poor intra-operative documentations of nervus transecting/injury or not, could touch prediction of the final outcome. Second, the data were collected retrospectively on a minor sample size and with no EMG study and Speech Language Pathology assessment. Finally, a option bias exists. Most patients seeking medical therapy after greater than six months of glottic incompetence may have been more likely to accept the need for surgical intervention, compared to the patients that were motivated to undergo early on intervention in the form of injection in the part.

Conclusions

This ten-year longitudinal assessment revealed that patients who received a temporary song fold injection for a newly diagnosed song fold immobility (less than half-dozen months) were less likely to undergo permanent medialization laryngoplasty (thyroplasty) compared with those patients who were treated with bourgeois management lone or had delayed treatment after vi months. Further studies with a voice communication language pathology assessment, EMG study and a longer lasting injectables such as radiesse™ for vocal fold paralysis are warranted.

References

-

Rosenthal LH, Benninger MS, Deeb RH: Vocal fold immobility: a longitudinal analysis of etiology over xx years. Laryngoscope. 2007, 117 (10): 1864-1870. x.1097/MLG.0b013e3180de4d49.

-

Mallur PS, Rosen CA: Vocal fold injection: review of indications, techniques, and materials for augmentation. Clin Exp otorhinolaryngol. 2010, iii (4): 177-182. 10.3342/ceo.2010.iii.4.177.

-

Flint Pw, Purcell LL, Cummings CW: Pathophysiology and indications for medialization thyroplasty in patients with dysphagia and aspiration. Otolaryngol–Caput Neck Surg. 1997, 116 (3): 349-354. x.1016/S0194-5998(97)70272-9.

-

Friedman AD, Burns JA, Heaton JT, Zeitels SM: Early on versus tardily injection medialization for unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Laryngoscope. 2010, 120 (x): 2042-2046. 10.1002/lary.21097. Comparative Study Inquiry Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

-

Damrose EJ: Percutaneous injection laryngoplasty in the management of acute vocal fold paralysis. Laryngoscope. 2010, 120 (8): 1582-1590. 10.1002/lary.21028.

-

Ford CN, Bless DM, Loftus JM: Role of injectable collagen in the treatment of glottic insufficiency: a study of 119 patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1992, 101 (3): 237-247. Enquiry Support, U.South. Gov't, Not-P.H.S. Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.

-

Mathison CCVC, Klein AM, Johns MM: Comparison of outcomes and complications between awake and asleep injection laryngoplasty: a case–control study. Laryngoscope. 2009, 119 (7): vii.

-

Bhattacharyya N, Batirel H, Swanson SJ: Improved outcomes with early on song fold medialization for vocal fold paralysis after thoracic surgery. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2003, xxx (1): 71-75. ten.1016/S0385-8146(02)00114-1.

-

Graboyes EM, Bradley JP, Meyers BF, Nussenbaum B: Efficacy and safe of acute injection laryngoplasty for vocal cord paralysis following thoracic surgery. Laryngoscope. 2011, 121 (11): 2406-2410. 10.1002/lary.22178.

-

Flint Prisoner of war, Downs DH, Coltrera Medico: Laryngeal synkinesis post-obit reinnervation in the rat. Neuroanatomic and physiologic study using retrograde fluorescent tracers and electromyography. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991, 100 (10): 797-806.

-

Siribodhi CSW, Atkins JP, Bonner FJ: Electromyographic studies of laryngeal paralysis and regeneration of laryngeal motor nerves in dogs. Laryngoscope. 1973, 73: 148-164.

-

Tashiro T: Experimental studies of the reinnervation of the larynx after accurate neurorraphy. Laryngoscope. 1972, 82: 225-236. 10.1288/00005537-197202000-00010.

-

Sulica 50: The natural history of idiopathic unilateral song fold paralysis: prove and problems. Laryngoscope. 2008, 118 (7): 1303-1307. 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31816f27ee. Review

-

Williams RG: Idiopathic recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis. J Laryngol Otol. 1959, 73: 161-166. 10.1017/S0022215100055110.

-

Paniello RC, Edgar JD, Kallogjeri D, Piccirillo JF: Medialization versus reinnervation for unilateral song fold paralysis: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Laryngoscope. 2011, 121 (10): 2172-2179. 10.1002/lary.21754.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Additional data

Competing interests

All authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

YA did the literature review, collected the data, aid in analyzing the data, wrote the abstract, introduction, discussion and conclusion. MR wrote the result department, help in information collection, analyze the information. KK: perform the injection and patients follow upwards, review the final manuscript. JY: perform injection and patients follow up, supervise all the article writing procedure and finally review the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' original submitted files for images

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Key Ltd. This is an Open up Access commodity distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/ii.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this article

Cite this commodity

Alghonaim, Y., Roskies, M., Kost, K. et al. Evaluating the timing of injection laryngoplasty for song fold paralysis in an attempt to avoid future type 1 thyroplasty. J of Otolaryngol - Head & Neck Surg 42, 24 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1916-0216-42-24

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1916-0216-42-24

Keywords

- Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve

- Vocal Fold

- Early on Group

- Vocal Fold Paralysis

- Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis

fredericminch1949.blogspot.com

Source: https://journalotohns.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1916-0216-42-24